Trade War

Newsletter 287 - Dec. 21, 2025

Trade War will be taking a break for the holidays, as will the weekly live video. Expect both back in mid January. See you in the new year!

Now on to the news ~

Welcome to the 287th edition of Trade War.

China’s retail sales eke out 1.3% growth in November, the weakest rate since 2022. Industrial production rises 4.8%, down from 4.9% growth a month earlier. And fixed asset investment drops 2.6% in the first eleven months of the year, worse than the 1.7% fall January through October.

Property investment continues its steep drop, plummeting 15.9% in the first eleven months. Real estate prices fall 2.8% in China’s largest 70 cities in November. And the overall urban employment figure of 5.1% mask weakness in the jobs market for young Chinese and migrant workers.

Beijing says it has granted new rare earth export licenses. Shenzhen court cracks down on smugglers of critical minerals. And rare earth sales to US drop 11% in November; that’s despite Trump claiming an agreement for their smooth flow was reached with Xi in October.

Notable/In depth ~

China discards “strategic restraint” with U.S. writes Zongyuan Zoe Liu, a Council on Foreign Relations Fellow for China Studies.

Chinese manufacturers now making “cutting-edge technology at prices that western competitors cannot match,” writes Chatham House’s James Kynge

Check out the Best China books of 2025, from Andy Browne, Managing Editor, Live Journalism at Semafor

Weakening across the board

Weakening across the board—that describes the disappointing economic numbers out from China earlier this week.

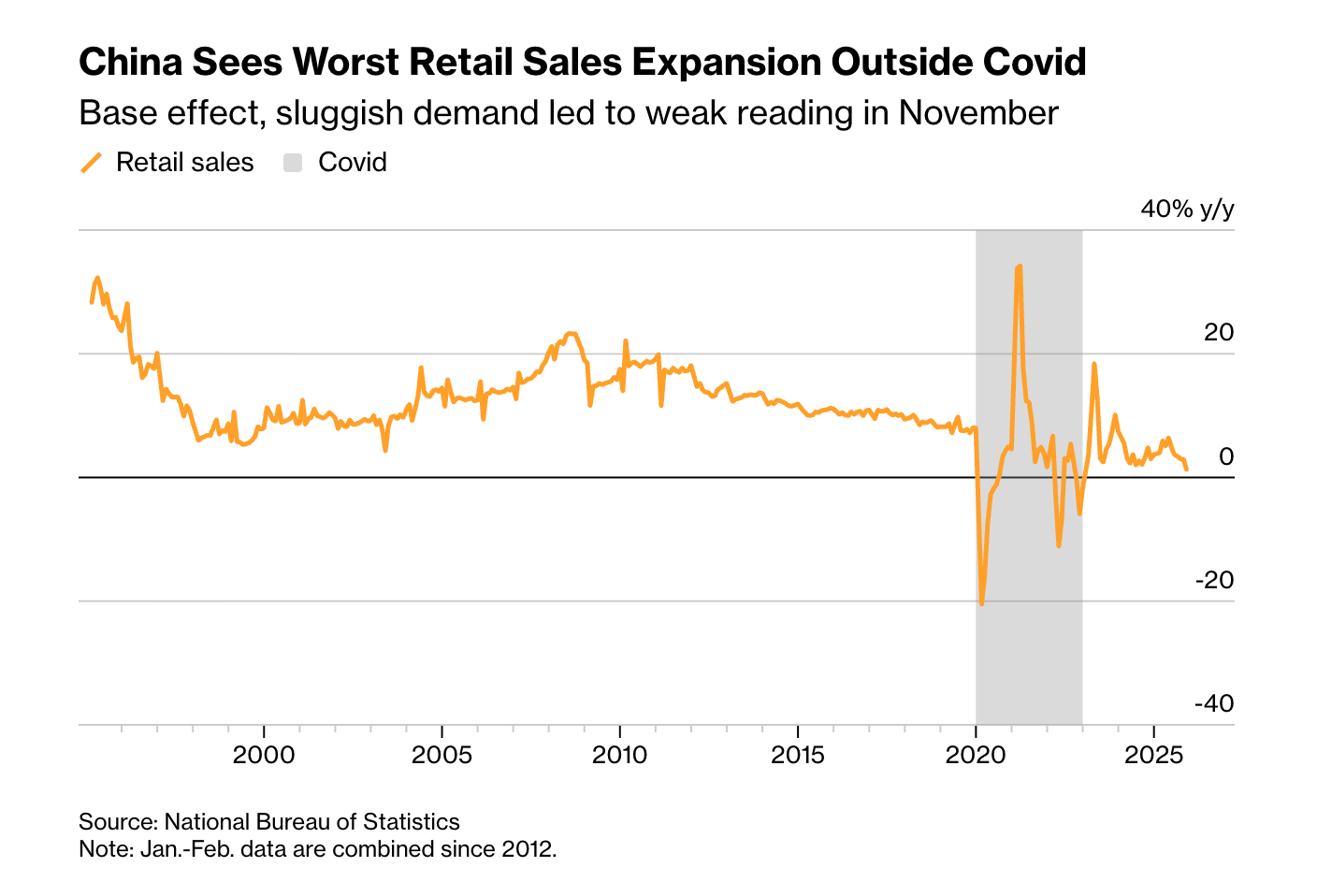

Retail sales worst since 2022

Probably most worrying is the drop in retail sales. That’s because they are a key measure of the progress made by the Chinese economy in transitioning away from its unsustainable reliance on debt, investment, and the struggling real estate sector, to one more driven by domestic demand.

Retail sales were their weakest since 2022, according to numbers released Monday by the China’s National Statistics Bureau. They were up only 1.3 percent in November, slowing from the 2.9 percent growth registered in October.

More shaky numbers:

Industrial production and property investment

Industrial production, although up 4.8 percent, is still showing a slowing trend, down from 4.9 percent growth in October. It’s also at its weakest level since the pandemic.

Fixed asset investment fell by 2.6 percent in the first 11 months of 2025. That’s worse than the 1.7 percent fall recorded in the January to October period and continues one of the worst investment declines seen in China’s history.

Property investment, the weakest part of fixed asset investment, continued to fall. It was down 15.9 percent in the period January through November, an even worse drop than the 14.7 percent recorded January through October.

Average prices in China’s 70 major cities fell by 2.8 percent in November, a bigger fall than October’s 2.6 percent drop.

Little progress on the job front

There has been limited progress in strengthening the job market. The official figure for registered urban unemployment in November was unchanged at 5.1 percent, the statistics bureau announced Thursday.

The youth unemployment rate for 16-to-24-year-olds, excluding students, remains at a much higher 16.9 percent (down from 17.3 percent the previous month and 18.9 percent over the summer, when recent graduates were seeking jobs).

Migrants and remittances

According to a Chinese economist friend who lives in Beijing but spends a considerable amount of time in the countryside, the employment situation is even worse in rural areas. He tells me that local officials are now trying to push migrants back to the cities because the job situation is so dire in China’s hinterlands.

A second reason for this move: many cash-strapped local officials can’t pay salaries to civil servants and are struggling to meet the social welfare promises they’ve made to the people. If the migrants return to the cities, officials are hoping they will once again send remittances home, helping plug gaps in local finances.

Of course, in recent years we’ve seen the reverse policy: officials in townships and villages have tried to lure migrants to come home, in the hope that their return would help drive economic growth in the poorer provinces they hail from.

Well, neither policy works any longer: there aren’t enough decent jobs in the cities or the countryside.

Rural underemployment

While the National Bureau of Statistics says that the unemployment rate for rural migrants is 4.4 percent, better than the registered urban unemployment rate of 5.1 percent, most of the jobs in the countryside are ill-paid and insecure gig positions.

I heard this from migrants back in Guizhou who were barely scraping by driving Didi cars or raising fish to serve to Chinese tourists visiting from the cities, when I was in the Southwestern province this past summer (I first met these migrants over 25 years ago and wrote about their lives in my 2020 book The Myth of Chinese Capitalism).

Export-driven growth can’t last forever

The one part of the economy that has until now held up is exports. But that is not sustainable.

Instead, there will be increasing pushback from countries around the world that are being flooded by Chinese electric vehicles, solar panels, and electronics.

As the head of the IMF Kristalina Georgieva warned China on a recent trip to Beijing, “continuing to depend on export-led growth risks furthering global trade tensions.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Trade War to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.